A Comparative Study of AryaVarta chronicles,the great Indian Novel and Ajaya

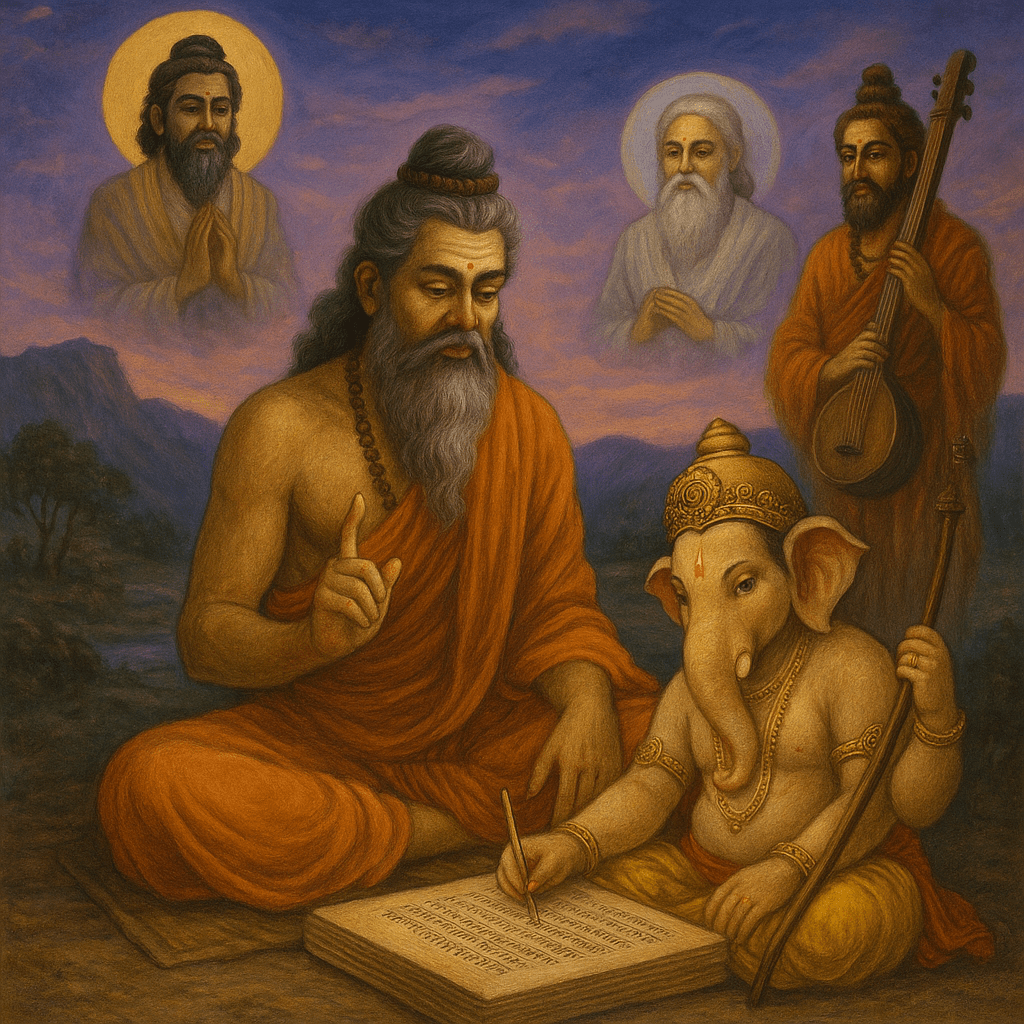

Vyasa, the sage traditionally conceived as both composer and narrator of the Mahābhārata, represents not only divine authority but also the ultimate power of authorship. In contemporary reimaginings, however, his role is radically destabilized, transformed into a figure through which questions of power, politics, and narrative authority are interrogated. Krishna Udayasankar’s Aryavarta Chronicles, Shashi Tharoor’s The Great Indian Novel, and Anand Neelakantan’s Ajaya series each stage Vyasa differently, aligning him with the authors’ distinctive aesthetic and ideological projects. Read comparatively, these portrayals illuminate the shifting concerns of modern Indian literature: the demythologization of tradition, the satirical critique of politics, and the reclamation of marginalized voices.

In Udayasankar’s Aryavarta Chronicles, Vyasa emerges as a profoundly humanized strategist, stripped of his divine aura and recast as Krishna Dwaipayana Vyasa, scholar-sage and custodian of esoteric knowledge. He is positioned at the nexus of politics and philosophy, orchestrating events to preserve Aryavarta’s precarious balance of power. His manipulation of secrets, alliances, and narratives situates him less as a detached chronicler and more as a political actor whose compromises embody the costs of statecraft. The tension between Vyasa and Govinda Shauri (Krishna) sharpens the thematic exploration of pragmatism versus idealism, secrecy versus transparency, and duty versus the greater good. Udayasankar’s Vyasa is thus a figure of epistemic authority but also of ethical ambiguity, foregrounding the fragility of human agency in a rationalized epic landscape.

By contrast, Tharoor’s The Great Indian Novel situates Vyasa in a satirical register, transforming him into V.V. (Ved Vyas), a retired civil servant and self-conscious narrator. Unlike Udayasankar’s political manipulator, V.V. functions as a framing device whose memoir-like storytelling reinterprets the Mahābhārata through India’s twentieth-century political history. Tharoor’s Vyasa does not direct events but comments upon them, embedding irony, parody, and bureaucratic detachment into the narrative voice. His perspective is not divine revelation but historiographic reflexivity, foregrounding the ways in which myth and history are mutually entangled. By appropriating Vyasa as a satirical chronicler, Tharoor underscores the cyclical follies of power and the absurdities of postcolonial politics, while simultaneously destabilizing epic grandeur through parody.

Neelakantan’s Ajaya series offers perhaps the most radical departure, recasting Vyasa as a symbol of narrative partiality rather than as an authoritative voice. In a project overtly revisionist, the series narrates the Mahābhārata from the Kaurava perspective, thereby exposing the politics of memory and narrative control. Vyasa, here, is not central to the plot but functions as a metatextual presence—the author of the Jaya whose “victor’s history” privileges the Pandavas while silencing the Kauravas. Unlike Udayasankar’s active political agent or Tharoor’s ironic memoirist, Neelakantan’s Vyasa becomes an emblem of historiographic violence: the manner in which epic tradition reproduces caste hierarchies, justifies power structures, and marginalizes dissenting voices. He is less a character than a contested site, the embodiment of narrative bias and its socio-political consequences.

Taken together, these three reimaginings chart a spectrum of responses to Vyasa’s authority. Udayasankar relocates him within the rational domain of politics, dramatizing the ethical burdens of knowledge and secrecy. Tharoor converts him into a satirical narrator, parodying both epic authority and modern political excess. Neelakantan destabilizes him entirely, using his authorial shadow to interrogate the victors’ monopoly over narrative truth. If Udayasankar’s Vyasa embodies the strategist, Tharoor’s enacts the satirist, and Neelakantan’s symbolizes the problem of historiography, then collectively they demonstrate that Vyasa is not merely a character but a metanarrative construct—an enduring reminder that storytelling is inseparable from power.

Footnote: Comparative Grid of Vyasa’s Reimaginings

| Author | Role/Function | Key Traits | Thematic Focus | Narrative Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Krishna Udayasankar (Aryavarta Chronicles) | Humanized strategist, scholar-sage | Secretive, burdened, pragmatic | Power, secrecy, human agency | Drives political intrigue; moral ambiguity underscores costs of leadership |

| Shashi Tharoor (The Great Indian Novel) | Satirical memoirist (V.V.), framing narrator | Witty, ironic, reflective | Political critique, myth-history entanglement | Commentary rather than participation; destabilizes epic grandeur |

| Anand Neelakantan (Ajaya Series) | Symbol of narrative authority and bias | Distant, shadowy, contested | Perspective, truth, marginalized voices | Embodiment of victors’ history; critiques historiographic violence |

Leave a comment