From whispered mystics to broadcast certainty, and the enduring cost of choosing comfort over courage

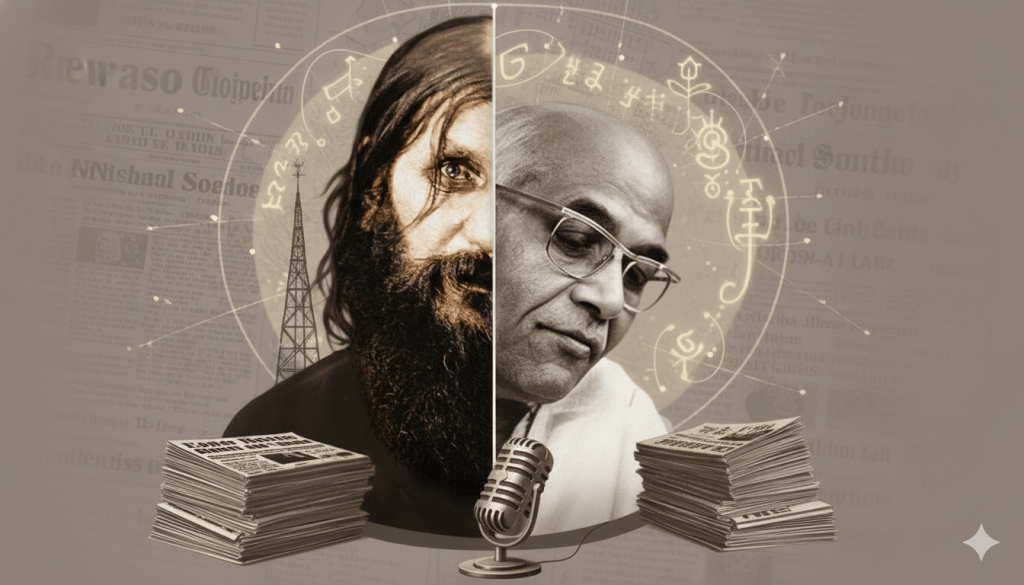

Rasputin and Goenka: Two Faces of Influence

On a winter night in late December 1916, Grigori Rasputin was killed by men who believed they were performing an act of rescue. He was poisoned, shot, beaten, and thrown into the frozen Neva — a death as theatrical as the life that preceded it. History often treats this assassination as a lurid footnote, but its significance lies elsewhere. Rasputin was not removed because he governed poorly or ruled unjustly. He was removed because he had come to matter more than institutions — a detail empires usually notice too late.

Rasputin held no office. He commanded no army. His power was informal, intimate, and unregulated. It travelled through whispers and confidences, sustained by mystique and fear. In a Russia exhausted by war and uncertainty, he offered reassurance masquerading as insight. The royal family tolerated him not because he was credible, but because he was comforting — and comfort, when scarce, is often mistaken for wisdom.

Rasputin was not an aberration. He was a social creation. Societies cultivate such figures when complexity becomes unbearable and scrutiny feels like an inconvenience. Distortion is rarely imposed at first; it is accommodated. It survives because it soothes. It flourishes because it simplifies. By the time violence enters the story, the rot has already been normalised.

A century later, influence has changed its form but not its character. It no longer needs to whisper. It broadcasts.

Where secrecy once conferred power, saturation now does. Influence today is built through repetition — constant presence, familiar certainty, the comfort of hearing the same thing everywhere. The danger is no longer silence, but noise. Not censorship, but choreography. When everything is amplified, discernment quietly exits the room.

This shift has produced a new class of intermediaries. They are not priests in private chambers or mystics in royal courts. They are performers of conviction, translating authority into certainty and complexity into slogans. Their legitimacy flows not from accountability but from reach. They do not persuade through argument; they prevail through ubiquity. Being correct is optional. Being omnipresent is essential.

India has encountered this pattern before. During the Emergency, alongside overt coercion, there emerged figures who offered reassurance, access, and moral cover to power. Chandraswami, the self-styled godman who moved easily through elite circles, was one such figure. Like Rasputin, he held no mandate and answered to no institution. His influence rested on proximity, mystique, and the unspoken understanding that power, when insecure, appreciates spiritual endorsement. He did not shape the Emergency; he thrived within its distortions — which is often how such figures prefer it.

Against this lineage of influence stands Ramnath Goenka.

Goenka did not whisper into power; he confronted it. He did not cultivate access; he maintained distance. During the Emergency, when silence was enforced and obedience presented as stability, he chose resistance that was visible, costly, and deliberate. His newspapers published blank editorials when words were forbidden, fought legal battles that invited reprisal, and absorbed personal risk without theatrics. There was no mystique in his method — only clarity of purpose.

Goenka understood influence as responsibility. Where Rasputin calmed authority, Goenka unsettled it. Where Rasputin thrived on belief, Goenka relied on credibility. One reassured rulers that all was well; the other insisted on documenting that it was not. One survived by becoming indispensable to power; the other by refusing to be useful to it.

Both forms of influence coexist in every era. They adapt easily to technology and temperament. Rasputin-like figures today no longer require private chambers; screens suffice. Their certainty is broadcast, their confidence contagious, their accountability negotiable. Goenka-like figures, meanwhile, appear rarer not because courage has vanished, but because courage is expensive — and few systems are eager to subsidise it.

Indian tradition recognises the value of restraint. The winter period of Dhanurmasa encourages inwardness, discipline, and pause. It cautions against impulsive action and unexamined speech. But restraint has never meant surrender. There are moments — political winters — when silence ceases to be wisdom and becomes complicity. Goenka understood this difference instinctively. He knew that there are seasons when quiet reflection is virtuous, and others when it is evasive.

As the year closes, it is tempting to treat figures like Rasputin and Goenka as historical curiosities — one grotesque, the other heroic. That would be comforting, and therefore misleading. They are not accidents of history; they are products of collective consciousness. Rasputins are cultivated by exhaustion, fear, and the desire to be reassured. Goenkas are sustained by vigilance, courage, and an acceptance that discomfort is a civic duty.

The choice between them is rarely dramatic. It is made quietly, daily — through what we tolerate, what we share, and whom we choose to listen to. Influence does not merely rise; it is rewarded. The only enduring question is whether we continue to reward those who soothe power, or those who insist on speaking to it plainly.

Footnote: Two Faces of Influence

| Rasputin | Goenka |

|---|---|

| Influence through proximity | Influence through distance |

| Thrived in mystique | Operated in transparency |

| Calmed power | Challenged power |

| Relied on belief | Relied on credibility |

| Cultivated by fear and fatigue | Sustained by vigilance and courage |

Author’s Note

This essay uses historical figures as metaphors rather than moral absolutes. Rasputin and Ramnath Goenka are not presented as anomalies, but as products of the social and institutional climates that enabled them. The intent is not to draw direct equivalences across eras, but to examine recurring patterns of influence — how power is soothed, how it is challenged, and how societies participate in sustaining both. Any parallels to the present are offered as reflections, not prescriptions.

Leave a comment