The notification blinked with all the empathy of a brick: “Lost connection!”

“I told you Ptah was a literal thinker,” Akshara said, stirring his tea like it had personally offended him, “but strangely, this time he’s being inferential.”

Ptah nodded gravely. “What he means,” the god clarified, unhelpfully, “is that he has lost connection with the people in his life.”

This, inevitably, reminded Akshara of P. G. Wodehouse—because when life collapses, British farce is the only reasonable refuge. Bertie Wooster and his friend Motty surfaced in his mind.

“What ho!” said Motty.

“What ho! What ho!” replied Bertie.

“What ho! What ho! What ho—”

“Good that Wodehouse stopped there,” Ptah observed. “It would have been rather difficult to carry a conversation beyond that.”

From the next table, reality leaked in uninvited.

“There was this great chasm I fell into,” a voice droned. “No way out. Work—dead end. Marriage—divorce procedure on. Kids—on the chopping block. Hell hath no fury like Fortuna offended.”

“What did you do about it?” someone asked.

Akshara leaned in despite himself. What did the blighter do about it? In retrospect, he wondered what the entire year had been about. It had started so promisingly—seminars, workshops, masterclasses (the post-COVID euphemism for PowerPoint fatigue). There was the course he was conducting at FLAME Institute of Liberal Arts.

As he sipped his tea, visions rose unbidden: FLAME University tucked away in a valley outside Pune, serenely insulated from the noise of ambition. He was lecturing on legitimacy, using the mythology of Kunti and Karna. Akshara had always possessed an inconvenient talent—the ability to actually see what myths embodied, not just footnote them.

Jarjara puja surfaced in his mind: the honoring of the arbor mundi. A whimsical smile crossed his face as he recalled chanting:

moolatah brahm rupaya

madhyavathe Vishnu rupena

agratah Shiva rupaya

vrksha rajayate namah

“Are we talking about tree worship?” a student had asked.

“Ethno-culture,” another had offered, helpfully vague.

“Anything works,” Akshara had replied. “Hinduism talks of thirty-three thousand gods.”

“Hey—you blabbered without believing a word of it,” said a familiar voice.

Akshara jumped. “Can you at least be visible?”

“Yes,” the voice replied, mildly offended. “If you ask respectfully. After all, I am God.”

“Ptah! Can you manifest?” Akshara demanded.

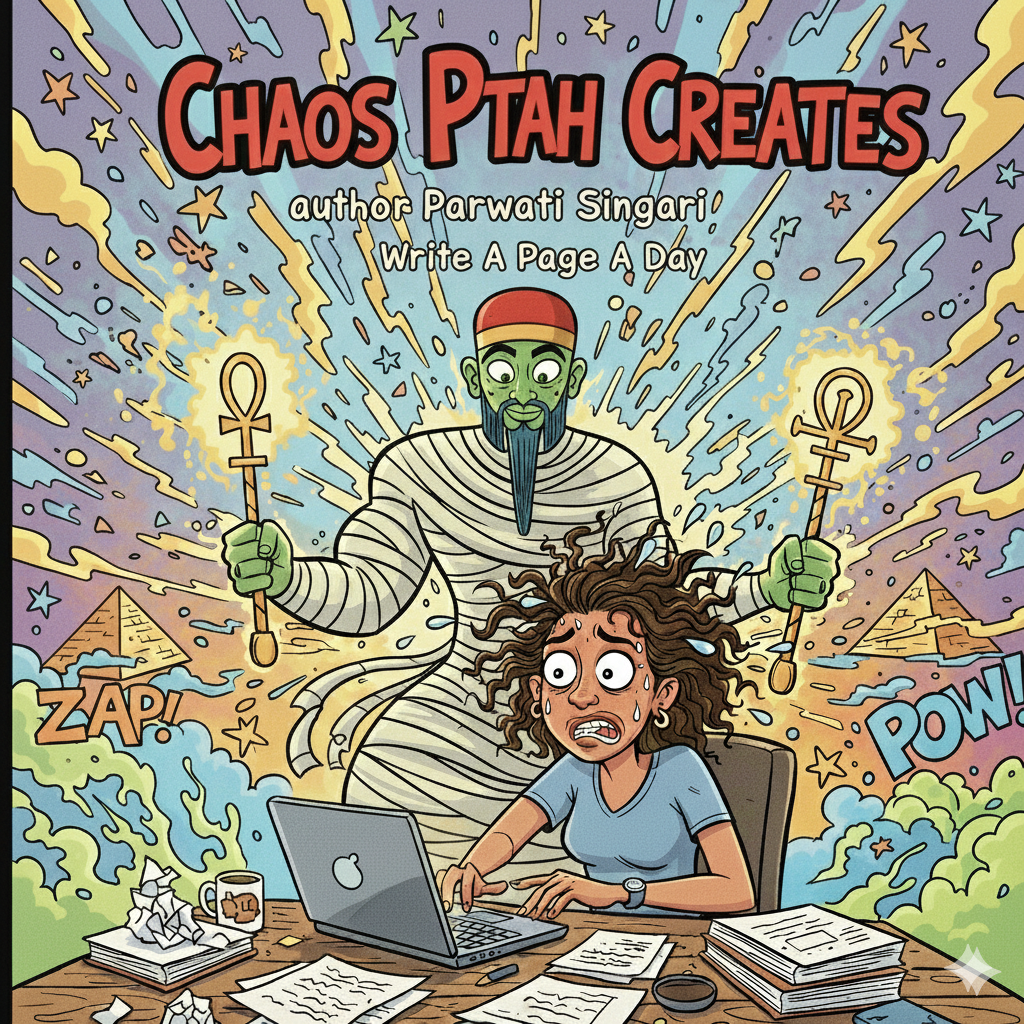

“Not bad,” Ptah said, materializing from a cloud with bureaucratic reluctance. “But next time, be polite.”

Akshara nearly burst out laughing. Ptah now stood fully visible—an Arab businessman’s suit topped with a pharaoh’s headgear.

“What the… hell… Ptah!”

Patiently, the god regarded him. “You lost your words today. That’s what happened in your session. You could not see, so there were no words. Or was it no words, so you could not see?”

That irritated Akshara more than it should have.

“Out of vulgar curiosity,” Ptah continued, “do you know why you’ve lost your words?”

Akshara said nothing.

“The Matrikas,” Ptah said gently. “The phonetics have left you. If you need proof, look at your messages—no vowels at all.”

Akshara glanced at his phone.

Lost connection indeed.

Leave a comment