Plimsoll Day, Tom & Jerry Launch Day, and “All That Can Fit in Print” Memorial Day

No one remembers who declared February 10th a day of significance.

Which is precisely why it now carries three dedications.

Tom called it historic.

Jerry said history was merely gossip that outlived its witnesses.

They stood beneath a banner listing the day’s observances:

- Plimsoll Day

- Launch of Tom & Jerry (Reimagined for the Attention Economy)

- All That Can Fit in Print Day (Observed, Not Believed)

“Too many dedications?” Tom asked.

“No,” Jerry replied. “Too little meaning. Dedications are cheaper than accountability.”

There was a time when newspapers upheld a dangerous assumption:

that anything which could fit into print deserved to be trusted.

This was before print discovered how efficiently it could shrink without disappearing.

In school, students followed the news the way they followed assembly prayers—standing upright, eyes forward, comprehension optional. They were taught to read headlines, not interrogate them. Analysis was mistaken for dissent and discouraged accordingly.

“We were trained,” Jerry observed, “to read without thinking. So now we think without reading.”

News now exists as ambience. Televisions remain switched on long after curiosity has left the room. Violence scrolls past in neat fonts. Crime statistics flicker briefly, like an inconvenience, before being replaced by something louder, brighter, and less demanding.

“If people actually listened,” Jerry continued, “to data-heavy voices—Ajay Prakash, for instance—the rise in violence wouldn’t feel shocking. It would feel structural.”

Tom frowned. “Structure doesn’t trend.”

“Neither does silence,” Jerry said, “but you broadcast that daily.”

Thus emerged All That Can Fit in Print Day—a ceremonial remembrance for a sentence no longer spoken aloud. It now joins other discarded beliefs, such as photographic truth and political memory.

Eyeballs, after all, are the new editors.

The launch proceeded as scheduled.

Tom embodied legacy media: dignified, bruised, legally alert.

Jerry represented citizen journalism: fast, decentralised, and frequently convinced that speed was a substitute for accuracy.

“Citizen journalism gives everyone a voice,” Tom announced.

“Yes,” Jerry agreed. “Including the ones that should be clearing their throats instead.”

At that moment, a man stormed the stage.

“I DEMAND THIS DAY BE CORRECTED.”

It was Sam Plimsoll.

“Today honours reform, ethics, and maritime safety,” he declared, “not that Wodehouse invention—Plimsoll—the bungling antithesis of Jeeves!”

The room blinked, mistaking recognition for understanding.

“They’ve turned seriousness into farce,” Plimsoll said. “History into content. Integrity into a mislabelled joke.”

Tom attempted diplomacy. “Sir, this is a launch.”

“Exactly,” Plimsoll replied. “Nothing is ever understood anymore—only launched.”

Jerry glanced at his phone.

“You’re trending,” he said.

“For what?” Plimsoll asked.

Jerry paused. “For being confused.”

Plimsoll sat down. “That explains everything.”

And that, officially, is what February 10th signifies.

Plimsoll Day reminds us that gravity is easily misfiled.

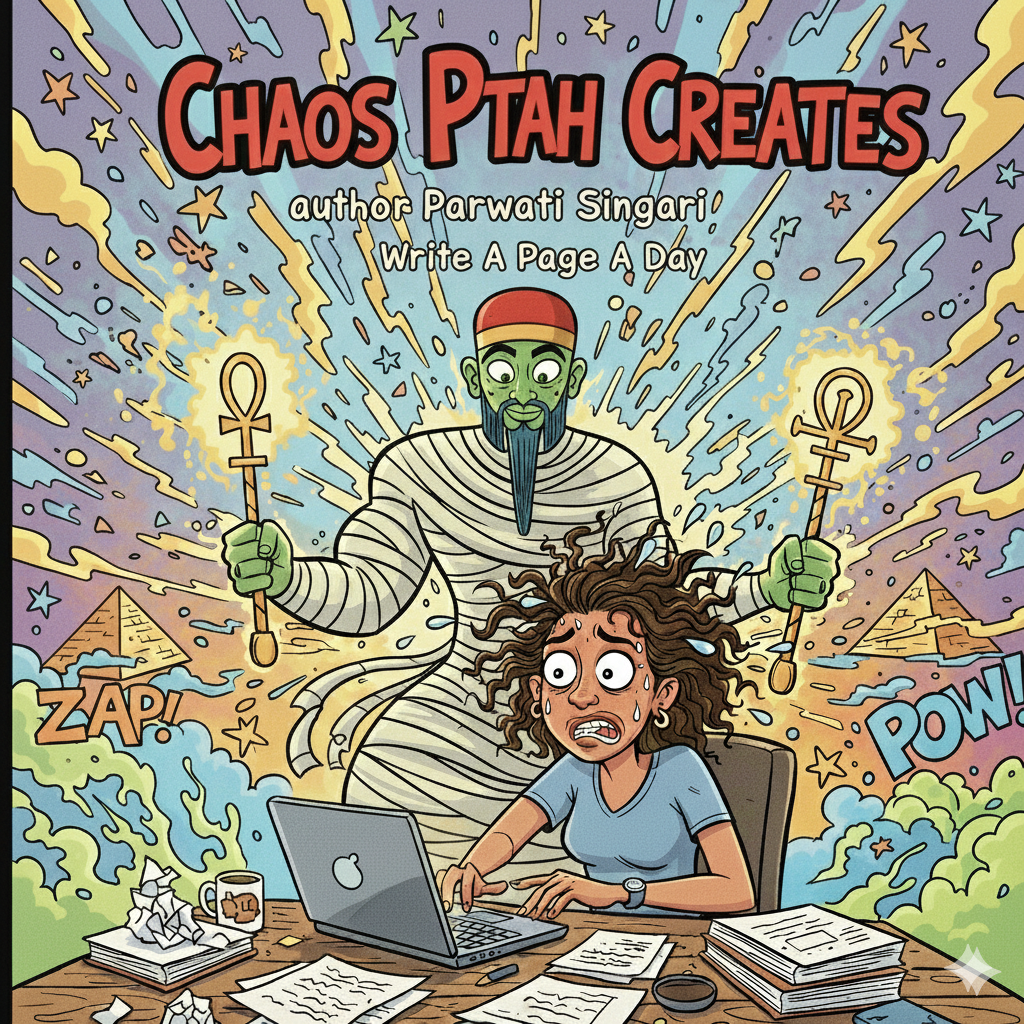

Tom & Jerry Day reminds us that chaos scales well.

All That Can Fit in Print Day reminds us that credibility once had dimensions.

Together, they commemorate the modern news cycle:

where meaning is ceremonial, outrage is operational, and truth—if it appears at all—must do so briefly, dramatically, and preferably sideways.

The launch was declared a success.

No one read the article.

Everyone observed the day.

Tomorrow’s news began warming up in the background.

Footnote

- None of the above occurred on February 10th, or on any other date. Tom and Jerry were never present, Plimsoll did not speak, newspapers remain widely trusted by people who agree with them, and this article exists solely to give structure to a feeling that could not otherwise be printed.

Leave a comment