Write a Page a Day: Minutes from the Department of Emotional Compliance

“Working relationship, but we never worked the relationship.”

Akshara said it like he was presenting Q4 losses in the Monday review. The pantry smelled of burnt coffee and inherited trauma.

His father, who functioned as legacy management, looked up from his newspaper. “Wow. What an insight. Which TED Talk vomited that into you?”

“Kamala-ajji.”

Silence.

“That woman,” his father muttered, the way HR says “culture issue.”

Kamala-ajji, according to family folklore, was “possessed.” As a child, Akshara had been told her eyes turned glassy, like a corrupted Excel sheet. His father had once whispered, “It’s as if her mother peeps through her.” Young Akshara had immediately replaced her face with a still from a Veerana marathon by the Ramsay Brothers and refused to visit her after sunset.

Years later, someone sensible had explained: “It’s called aging. You become your parents with better PR.” That had calmed him. Possession sounded dramatic. Intergenerational conditioning sounded billable.

At work, conditioning was called “alignment.”

The Landmark coach—Venugopal, yes, that was his name—had once diagrammed it beautifully: “We open to new information, integrate, stabilize worldview.” Akshara had nodded like a man who understood verbs.

His grandmother had sworn by coconut oil. Saffola had sworn by cholesterol anxiety. His own Google search had sworn by confusion. Between tradition, advertising, and algorithm, he had become a product prototype.

Mass-produced doubt.

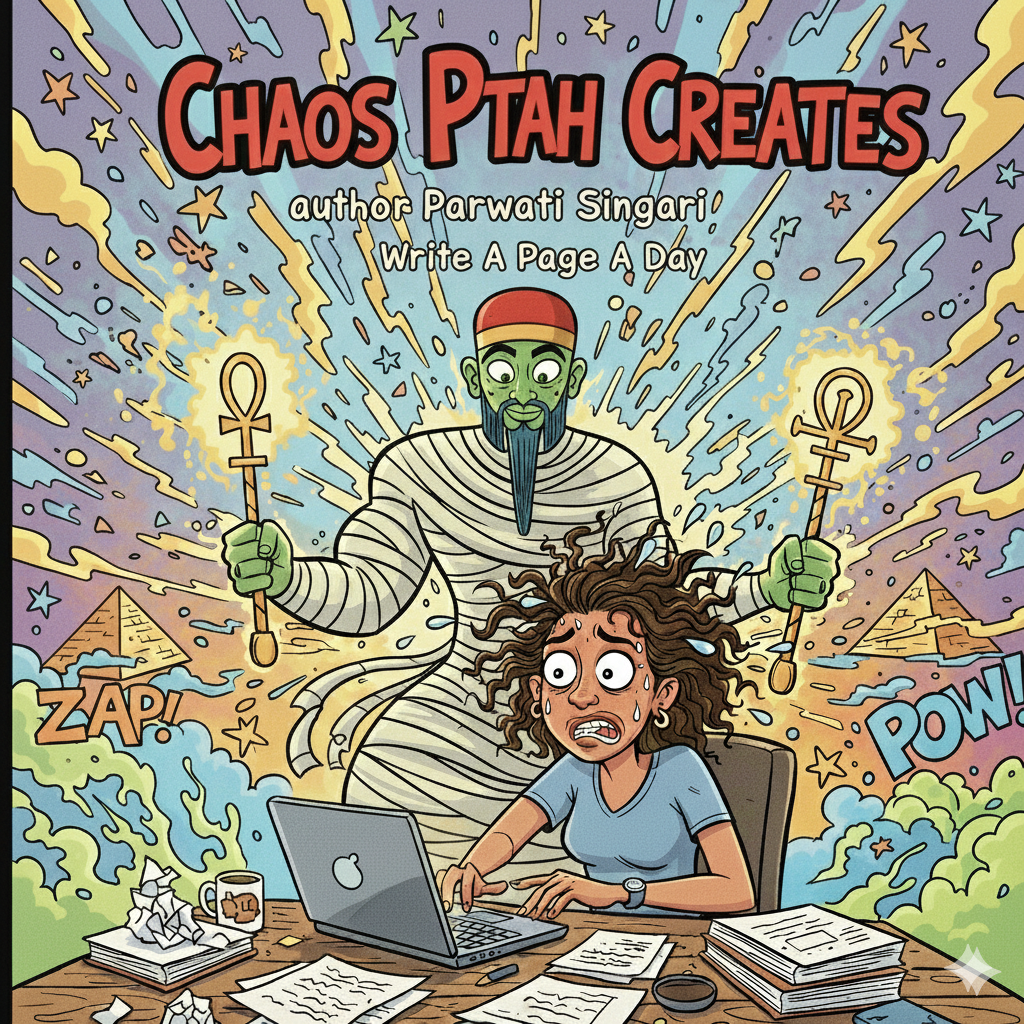

And yet his core issue remained embarrassingly unchanged: he wasn’t blocked, as Ptah insisted. He was lost.

Lost in a cubicle with ergonomic despair.

He had been flirting with the idea of quitting—freelancing, consulting, becoming one of those LinkedIn prophets who use the word “pivot” as a noun. But the salary came on time. The ID card opened doors. Security was a warm, padded cell.

Yesterday evening, Ishwari from Compliance—also the unofficial tarot reader—had spread cards across the conference table between two stale doughnuts. He had drawn the Ace of Swords.

“Imagine a soldier,” she intoned, “poised to attack or defend. Is your next move reactive or proactive?”

Reactive was replying-all at 11:47 p.m.

Proactive was resigning.

He felt bullied by something—expectation, perhaps. Or the silent accusation of potential. If he could identify the enemy, he would gladly brandish the sword. Instead, he refreshed his inbox.

He could imagine Ishwari brandishing a sword at her mother-in-law. He could imagine himself brandishing one at his boss during appraisal season. But at Ptah? Impossible.

Ptah didn’t sit across a desk. Ptah occupied the swivel chair of his conscience.

“Sonny boy,” Ptah said now, leaning back in the ergonomic throne of inherited wisdom, “boundaries are not rebellion. Listening is not default obedience. It is data processing.”

Akshara rolled his eyes internally.

“It’s very convenient,” Ptah continued, “to let boss, father, horoscope, market trends decide. Then you get to say—‘Not my decision.’ That is the backdoor exit from adulthood.”

The office air-conditioning hummed like ancestral gossip.

“You blame Kamala-ajji. You blame your father. You blame the economy. You blame the cards. But ancestral wisdom is not a haunting. It’s a handover note.”

Akshara swallowed.

“Your elders are not possessing you,” Ptah said, smiling with terrible gentleness. “They are waiting to see if you will upgrade the software.”

“And if I don’t?”

“Then you will become the ghost in your own child’s pantry conversation.”

There it was. The sword.

Not to attack father. Not to defend ego.

To choose.

To take responsibility for the next line on his own balance sheet.

Outside, someone asked loudly, “What’s the difference between reactive and proactive?”

Akshara closed his laptop.

“Salary,” he muttered. “And spine.”

He outsourced every decision-

until even his regrets required managerial approval.

Leave a comment